A 20-kilogram blend of industrial-strength ammonium nitrate, sugar, and acetone peroxide explodes in the cherished Place de la Vendôme in central Paris. The bomb, assembled by a far-left terrorist cell, sets off hundreds of meters of destruction, felling the square’s famed column and damaging many of the surrounding government buildings, including the Ministry of Justice.

None of this has happened, of course. It’s one scenario sketched out—on a speculative color-graded map, no less—by the Paris police department’s explosives expert on October 11, one week into France’s first far-left anti-terrorism trial since the 1990s. (The infamous Tarnac 9 case of 2008 was never actually brought to trial for terrorism and ended with a full acquittal 10 years later.)

The defendants of the so-called “affaire du 8 décembre”—a reference to their 2020 arrest date—had no identifiable plan whatsoever to commit acts of violence against state institutions. Seven people are currently implicated, facing charges of association de malfaiteurs terroristes (association of terrorist criminals, AMT), or as the judge read out on October 3, in the vague language of France’s anti-terrorism laws, of “participat[ing] in a grouping or pact formed with a view to committing acts of terrorism.” (…) MT charges are the bread and butter of France’s anti-terrorism laws, yet critics note that they transfer the burden of proof onto defendants. The accused are being judged not for concrete acts but for intentions attributed to them. “It’s not so much about the substance of the facts,” says Laurent Bonelli, a sociologist of terrorism and radicalization. With an AMT, “the job of investigators and prosecutors is to connect the dots, to tell a plausible story that can back up the hypothesis of terrorist conspiracy. They have to write a realistic fiction.” At what point can one ascribe criminal intentions to a joke about killing a police officer? Simon was grilled on October 6 for a February 2020 conversation in which Florian said of the police, “They kill us. They mutilate us,” before imagining what he’d do if a hypothetical police officer was pushed over by a crowd of demonstrators. “I’d kick him in the face,” said Simon, to which Florian replied, “Nah, I’d kill him.” Dumbfounded, Simon explained to the judge: “It’s sad to say, but put two drunk leftists in a van and this is what you get. The words don’t really mean much.”

Even if drunken conversations putting the world to rights could really be considered evidence, the trial dossier is riddled with inconsistencies, as the group’s defense counsel has painstakingly pointed out. “You really have to watch out on YouTube,” the case file erroneously cites Florian as having said—implying he suspected they were being surveilled—which the defense corrected to “take a look on YouTube.” Three weeks into the trial, and police investigators have still not testified before the court. There are long gaps and an apparently cherry-picked narrative; excerpts hours apart are read in court as if from the same conversation.

According to the case file: “At 10.05pm, after a disconnected conversation, [Florian] cited the necessity of guerrilla struggle: ‘My absolute priority in life, at the moment, is that… Yeah I’m on it… But being two isn’t enough. You have to think of it as war.” Of his romantic life, Florian said: “I always told [my girlfriend], I’m not in a couple, the absolute priority is the cause, you’ll always be second to that.” CEOs should keep in mind that they could “take a bullet,” Simon had joked half an hour earlier, alluding to the 1986 assassination of Renault CEO Georges Besse by the far-left militant group Action Directe. “We’re only discussing the recordings that were transcribed by investigators,” Kempf told The Nation. “I’ve calculated that over the whole period between February and December…the prosecutor has taken 0.72 percent of the daily life of my client. They’re taking a few isolated conversations at specific moments where he’s making explosives and talking with friends about violent protests.”

Indeed, as the defendants have taken the stand, it would seem that their activism, lifestyle, and class position is what’s on trial. Irregular employment histories, involvement in ecological activism and land occupations, itinerant lifestyles (living in vans or squats), being a vegetarian, being a previous victim of police violence, writing a master’s thesis in literature about representations of war, involvement in a punk scene: These are all things the prosecution has raised in its attempt to make terrorists of the seven defendants.

(…) Politically, the trial of the December 8 group is about dusting off France’s anti-terrorism statutes to target activists on the left. Gérald Darmanin, President Emmanuel Macron’s draconian interior minister, has waged a concerted campaign to harass left-wing groups deemed “anti-republican” and “separatist.” The defendants in this case were arrested amid protests over Darmanin’s controversial global security law, which sought to increase police impunity amid a media campaign about threats to officers’ safety. France’s State Council, the highest administrative court, will soon rule on Darmanin’s order to dissolve the environmentalist collective Les Soulèvements de la Terre, a group he has accused of “ecoterrorism.” In an October 5 parliamentary hearing on violent political groups, he boasted that as many as 10,000 individuals associated with the far left are currently being followed by French intelligence services.

“Anti-terrorist justice has always been in lockstep with the political humors of the day,” says Bonelli. The acquittal of the Tarnac 9 was an embarrassing defeat for officials in France’s anti-terrorist hierarchy. What’s striking to observers this time around is that the state’s sensationalistic case seems even weaker.

“For the two weeks I’ve been at this trial, what have we seen? A group of benevolent, humane people who’ve done things that, yes, are not exactly legal, but that have nothing to do with terrorism,” says Olive, Camille’s father.

Hearings are slated to draw to a close by October 27, with an initial verdict expected shortly thereafter.

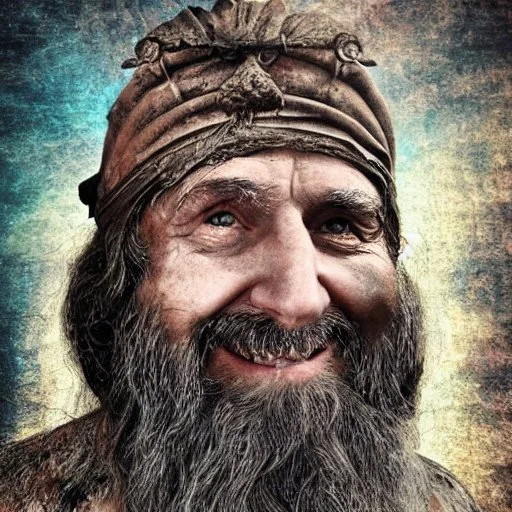

You can have a look at the “paramilitary training” here

You wouldn’t know her, she goes to another leftist group.